Liber Abaci

Liber Abaci (1202, also spelled as Liber Abbaci) is a historic book on arithmetic by Leonardo of Pisa, known later by his nickname Fibonacci. In this work, Fibonacci introduced to Europe the Hindu-Arabic numerals, a major element of our decimal system, which he had learned by studying with Arabs while living in North Africa with his father, Guglielmo Bonaccio, who wished for him to become a merchant.

Liber Abaci was among the first Western books to describe Arabic numerals, the first being the Codex Vigilanus completed in 976; another pivotal work followed by Pope Silvester II in 999. By addressing tradesmen and academics, it began to convince the public of the superiority of the new numerals.

The title of Liber Abaci means "The Book of Calculation". Although it has also been translated as "The Book of the Abacus", Sigler (2002) writes that this is an error: the intent of the book is to describe methods of doing calculations without aid of an abacus, and as Ore (1948) confirms, for centuries after its publication the algorismists (followers of the style of calculation demonstrated in Liber Abaci) remained in conflict with the abacists (traditionalists who continued to use the abacus in conjunction with Roman numerals).

Contents |

Summary of sections

The first section introduces the Arabic numeral system, including lattice multiplication and methods for converting between different representation systems.

The second section presents examples from commerce, such as conversions of currency and measurements, and calculations of profit and interest.

The third section discusses a number of mathematical problems; for instance, it includes (ch. II.12) the Chinese remainder theorem, perfect numbers and Mersenne primes as well as formulas for arithmetic series and for square pyramidal numbers. Another example in this chapter, describing the growth of a population of rabbits, was the origin of the Fibonacci sequence for which the author is most famous today.

The fourth section derives approximations, both numerical and geometrical, of irrational numbers such as square roots.

The book also includes proofs in Euclidean geometry. Fibonacci's method of solving algebraic equations shows the influence of the early 10th century Egyptian mathematician Abū Kāmil Shujāʿ ibn Aslam.[1]

Fibonacci's notation for fractions

In reading Liber Abaci, it is helpful to understand Fibonacci's notation for rational numbers, a notation that is intermediate in form between the Egyptian fractions commonly used until that time and the vulgar fractions still in use today. There are three key differences between Fibonacci's notation and modern fraction notation.

- Where we generally write a fraction to the right of the whole number to which it is added, Fibonacci would write the same fraction to the left. That is, we write 7/3 as

, while Fibonacci would write the same number as

, while Fibonacci would write the same number as  .

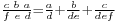

. - Fibonacci used a composite fraction notation in which a sequence of numerators and denominators shared the same fraction bar; each such term represented an additional fraction of the given numerator divided by the product of all the denominators below and to the right of it. That is,

, and

, and  . The notation was read from right to left. For example, 29/30 could be written as

. The notation was read from right to left. For example, 29/30 could be written as  , representing the value

, representing the value  . This can be viewed as a form of mixed radix notation, and was very convenient for dealing with traditional systems of weights, measures, and currency. For instance, for units of length, a foot is 1/3 of a yard, and an inch is 1/12 of a foot, so a quantity of 5 yards, 2 feet, and

. This can be viewed as a form of mixed radix notation, and was very convenient for dealing with traditional systems of weights, measures, and currency. For instance, for units of length, a foot is 1/3 of a yard, and an inch is 1/12 of a foot, so a quantity of 5 yards, 2 feet, and  inches could be represented as a composite fraction:

inches could be represented as a composite fraction:  yards. However, typical notations for traditional measures, while similarly based on mixed radixes, do not write out the denominators explicitly; the explicit denominators in Fibonacci's notation allow him to use different radixes for different problems when convenient. Sigler also points out an instance where Fibonacci uses composite fractions in which all denominators are 10, prefiguring modern decimal notation for fractions.

yards. However, typical notations for traditional measures, while similarly based on mixed radixes, do not write out the denominators explicitly; the explicit denominators in Fibonacci's notation allow him to use different radixes for different problems when convenient. Sigler also points out an instance where Fibonacci uses composite fractions in which all denominators are 10, prefiguring modern decimal notation for fractions. - Fibonacci sometimes wrote several fractions next to each other, representing a sum of the given fractions. For instance, 1/3+1/4 = 7/12, so a notation like

would represent the number that would now more commonly be written

would represent the number that would now more commonly be written  , or simply the vulgar fraction

, or simply the vulgar fraction  . Notation of this form can be distinguished from sequences of numerators and denominators sharing a fraction bar by the visible break in the bar. If all numerators are 1 in a fraction written in this form, and all denominators are different from each other, the result is an Egyptian fraction representation of the number. This notation was also sometimes combined with the composite fraction notation: two composite fractions written next to each other would represent the sum of the fractions.

. Notation of this form can be distinguished from sequences of numerators and denominators sharing a fraction bar by the visible break in the bar. If all numerators are 1 in a fraction written in this form, and all denominators are different from each other, the result is an Egyptian fraction representation of the number. This notation was also sometimes combined with the composite fraction notation: two composite fractions written next to each other would represent the sum of the fractions.

The complexity of this notation allows numbers to be written in many different ways, and Fibonacci described several methods for converting from one style of representation to another. In particular, chapter II.7 contains a list of methods for converting a vulgar fraction to an Egyptian fraction, including the greedy algorithm for Egyptian fractions, also known as the Fibonacci–Sylvester expansion.

Modus Indorum

In the Liber Abaci, Fibonacci says the following introducing the so-called "Modus Indorum" or the method of the Indians, today known as Arabic numerals.

- After my father's appointment by his homeland as state official in the customs house of Bugia for the Pisan merchants who thronged to it, he took charge; and in view of its future usefulness and convenience, had me in my boyhood come to him and there wanted me to devote myself to and be instructed in the study of calculation for some days.

- There, following my introduction, as a consequence of marvelous instruction in the art, to the nine digits of the Hindus, the knowledge of the art very much appealed to me before all others, and for it I realized that all its aspects were studied in Egypt, Syria, Greece, Sicily, and Provence, with their varying methods; and at these places thereafter, while on business.

- I pursued my study in depth and learned the give-and-take of disputation. But all this even, and the algorism, as well as the art of Pythagoras, I considered as almost a mistake in respect to the method of the Hindus. (Modus Indorum). Therefore, embracing more stringently that method of the Hindus, and taking stricter pains in its study, while adding certain things from my own understanding and inserting also certain things from the niceties of Euclid's geometric art, I have striven to compose this book in its entirety as understandably as I could, dividing it into fifteen chapters.

- Almost everything which I have introduced I have displayed with exact proof, in order that those further seeking this knowledge, with its pre-eminent method, might be instructed, and further, in order that the Latin people might not be discovered to be without it, as they have been up to now. If I have perchance omitted anything more or less proper or necessary, I beg indulgence, since there is no one who is blameless and utterly provident in all things.

- The nine Indian figures are:

- 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

- With these nine figures, and with the sign 0 ... any number may be written. (Sigler 2003 and Grimm 1973)

In other words, in his book he advocated the use of the digits 0–9, and of place value.

In this book he showed the practical importance of the new numeral system by applying it to commercial bookkeeping, conversion of weights and measures, the calculation of interests, money-changing, and numerous other applications. The book made an important contribution to the spread of decimal numerals, although as Ore writes this process was "long-drawn-out" and did not become complete until the later part of the 16th century.

References

- ^ O'Connor, John J.; Robertson, Edmund F., "Abu Kamil Shuja ibn Aslam", MacTutor History of Mathematics archive.

- Grimm, R. E. (1973), "The Autobiography of Leonardo Pisano", The Fibonacci Quarterly 11 (1): 99–104, http://www.fq.math.ca/Scanned/11-1/grimm.pdf.

- Sigler, Laurence E. (trans.) (2002), Fibonacci's Liber Abaci, Springer-Verlag, ISBN 0-387-95419-8.

- Ore, Øystein (1948), Number Theory and its History, McGraw Hill. Dover version also available, 1988, ISBN 978-0486656205.